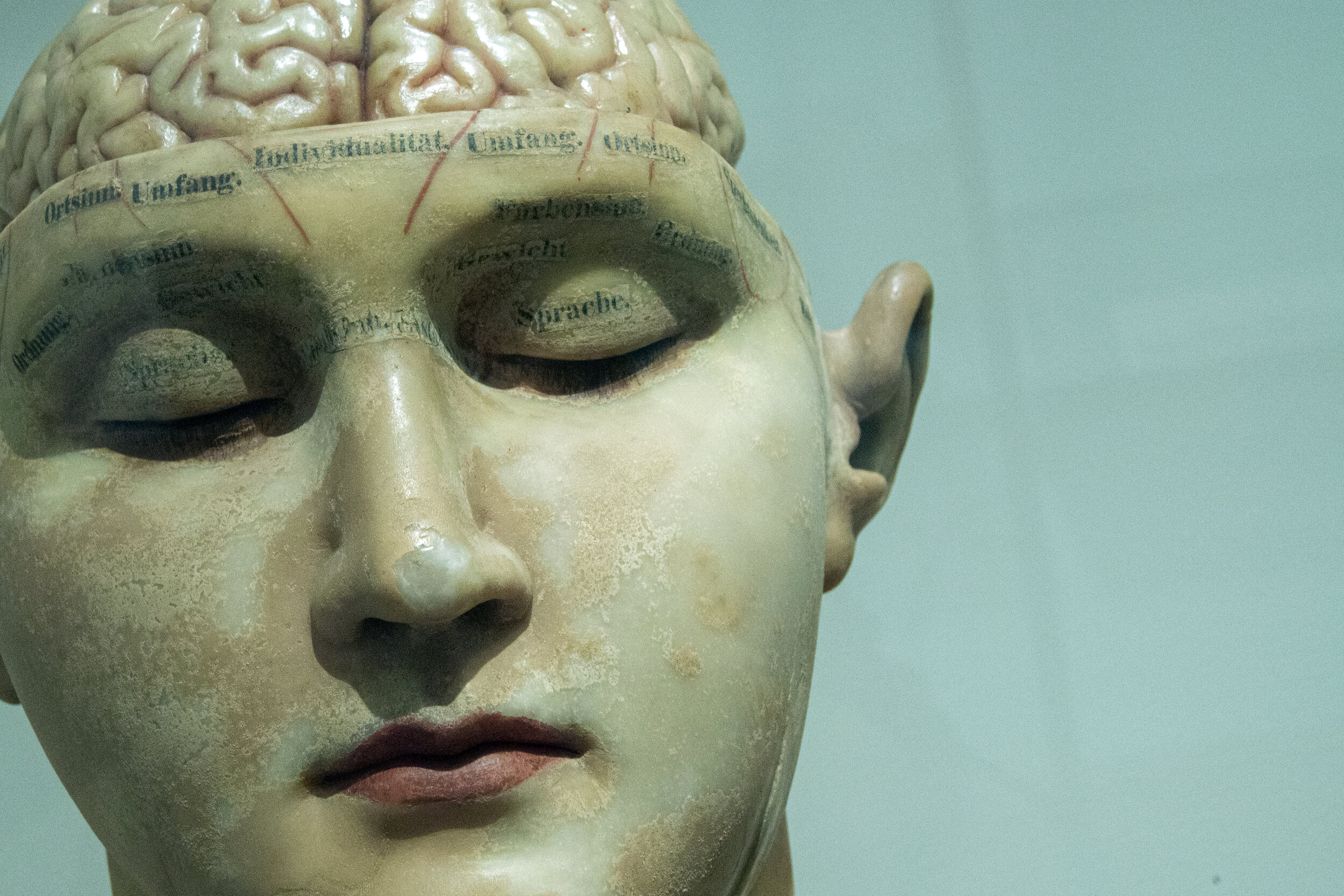

'It's all in your head.' - the comment we all heard before

It’s all in your head. I think I heard this hundreds of times when I tried to describe my symptoms to an outsider. And my reaction to it (as you can probably imagine) was frustration, rage even. I felt that I was not taken seriously, I was not heard, and I was somehow accused of causing my symptoms. I often said: if it was in my head, don’t you think I could fix it?

While I was doing my research looking at new, interdisciplinary fields in the intersection of neurology and psychiatry, these memories somehow popped up again. It was all in my head. While the comment is dismissive and hurtful, it has some unintended truth. It’s all in my head because my brain is in my head!

The brain is the only human organ which is studied by two separate fields: neurology and psychology. These started to move apart at the beginning of the 20th century, forming their own procedures, diagnostic criteria, textbooks, manuals, and even vocabulary. Essentially, this distinction led to the illusion that the study of behaviour and cognition is an entirely different matter than the brain’s and body’s neural networks and their activity. In our everyday thinking, a psychological problem somehow became a ‘softer’ issue, a problem with our thinking or not being able to control our emotions. A ‘neurological’ problem sounds much more severe somehow, and it is also detached from our experiences, cognition, and feelings. In other words, we are not responsible for it. The general assumption is that a neurological problem is a structural change in the brain due to genetic factors, medications or other external influences, therefore, we are the receivers of an impact over which we have no power.

Historically speaking, MFD was diagnosed as a type of hysteria for a long time, before it was re-classified as a neurological disorder in the late 1970s. Before that, musicians were told that it was ‘in their heads’ but they were not offered very little support. With the self-blame and guilt people generally experience after the onset, this diagnosis often left musicians in isolation and sent them spiralling down into depression. So in many ways, the new classification came as a relief. Having the hard science acknowledge the problem spelt the message: ‘No, it is not our fault! You’re not making this up!’ However, this U-turn in the classification did not result in a reliable solution.

While the boundary between neurology and psychiatry is clear in our heads, and we attach many ideas to each, the distinction is artificial. While having this system helps research and treatment in many ways, it is not very punctual in describing reality. As our understanding of the brain evolves, many of the previously widely accepted views were questioned or even debunked, especially the ones which attempted to understand the brain as a system of separate elements acting in isolation. For example, when tested with MRI, there is no evidence that the theory of being left-brain (analytical) or right-brain (artsy and imaginative) dominant is correct (see the article here), and the idea of having a reptilian brain responsible for the fight or flight response and aggression has been critiqued heavily by many researchers (you can read about this here).

As we start to see how different functions of the brain are intertwined (exciting article here), more and more connections are discovered between neurological and psychological conditions. Depression causes structural neural changes. Neurological conditions have co-morbid psychological issues in a high percentage of the cases. Similar circuits might be responsible for emotions and motor activity.

So what does this mean for us?

It means that it’s likely that emotions, cognition and the behaviours driven by them, do play a part in MFD. Does this make it out fault? Of course not.

Different environmental impacts and experiences can result in unconscious programming and changes the brain structure itself. As an example, childhood abuse can lead to a smaller hippocampus, corpus callosum and brain volume in general, and altered function and structure in the prefrontal cortex (read the article here). But even if we did not have such severe trauma in our past, our upbringing, social environment, personal experiences had a huge impact on how our nervous system developed, and as a result, on our psychology. Social neuroscience shows us how certain neurological problems can stem from our relationship to our social environment. Neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, and behavioural neurology are all aiming to understand how our brains work from a much broader and interdisciplinary viewpoint. Researchers and scientists are pursuing a new understanding which links neurology, social connections, experiences, and psychology.

How does this relate to us?

Translating ‘psychological’ to ‘it’s all your fault’ is understandable given the history of the treatment of MFD, but it is not helpful in terms of rehabilitation. Rejecting the psychological and behavioural dimensions of the condition might relieve some of the self-blame, but also make you powerless and victimised. Based on the evolving science looking at the interconnectedness between different functions of the brain and other impacting factors from our environment, turning towards our emotions, cognition, habitual behavioural patterns, traumatic memories and social relationships, can be an extremely helpful step in our rehabilitation. While there is no direct scientific evidence that this directly influences the motor symptom, in most of my cases, a holistic approach led to significant improvement in the playing technique. Mindfulness meditation, somatic approaches (yoga, Feldenkrais Method, etc), and breathing exercises are all useful tools to impact our entire system and decrease the symptoms as a downstream consequence. Therapy can be hugely helpful: my favourite approaches are Internal Family Systems (more info here) and the therapy based on Polyvagal Theory (listen to this episode or read about it the theory here or look into Deb Dana’s amazing work here), but any evidence-based approach can be beneficial.

Most of the fully recovered musicians I know used a mix of many different therapeutic tools - somatic and psychological: changing behaviours, observing not only their motor function but the accompanying emotions and thought processes. My main breakthrough in my recovery process was the result of introducing mindfulness to my daily life after reading Eckhart Tolle’s book, The power of now, which completely changed the way I worked on the instrument throughout my rehabilitation.

The phrase ‘it’s all in your head’ often comes from ignorance and fear. Do not let it stop you from doing what is beneficial to you.